Assessing open bike sharing data in Berlin

How is data currently being published, and how might the city benefit from the introduction of data standards?

The average Berliner spends an average of 154 hours a year sitting in traffic jams (INRIX Traffic Study (German)), leading the list of cities in Germany with the worst traffic. In the face of these realities, it’s no longer worthwhile to debate whether new transport concepts are needed but rather to focus on what these concepts should look like. Last year, Berlin passed a Mobility Law that paved the way for major improvements to the city’s cycling infrastructure. Among other things, by redesigning important junctions and the establishment of safe cycling facilities on all major roads, the number of seriously injured and fatalities should be reduced to a minimum (Vision Zero) and the car traffic by 2050 be climate neutral.

Bike- and E-Scooter-Sharing in Berlin

In addition to private bicycles, more and more bike sharing companies are taking up space on Berlin’s streets with their fleets of rental bikes. The most recent player to join the field is Uber, with their new Jump brand. The advantages are obvious: a bike can be borrowed quickly and easily, no need to own one yourself. As a result, car rides may be reduced. Annoying maintenance and theft risks of an own bike are eliminated. In addition, multimodal models can be better implemented: The rental bike can be used for the ride to the next S-Bahn stop, without having to worry about the further transport of the bike or the later “pick up”.

But these rental bikes are not being met solely with positive reactions. Many citizens are finding cause to complain, as they increasingly find rental bikes occupying and blocking space on sidewalks and public squares.

And now the shared mobility market in Germany is poised to get even more crowded: Germany’s Bundesrat, the federal legislative body representing Germany’s sixteen states, decided after a heated debate that, as of June 15, e-scooters will also be allowed on German roads. Opponents to this decision fear that now e-scooter-sharing operators will flood sidewalks with their devices, adding onto existing challenges with shared mobility services in German cities.

Based on the decision of the Bundesrat, rental bikes and now scooters are allowed to operate in Berlin as long as they aren’t “in the way” (such as blocking subway entrances or elevators), and defective vehicles must be removed within 24 hours. In Berlin, the individual Public Order Offices (Ordnungsämter) of the various boroughs are responsible for checking that these rules are upheld. For more information, see this article (German) as well as this one (German).

But what will this enforcement actually look like? The rise of data sharing agreements between shared mobility operators and city governments offers one possible answer: The tedious manual work of public officials checking up on individual bikes or scooters could be easily automated by operators providing location data for their vehicles to the Public Order Office in real time and digitally. Other cities are already making use of this potential, such as Los Angeles (USA), which sets mandatory standards for shared mobility operators with the Mobility Data Specification (MDS).

MDS: Mobility Data Specification

MDS defines how data related to rental bikes should be structured and provided. Moreover, it empowers cities to establish digitally defined prohibition zones where bikes cannot be parked, and to obtain historical data for further analysis. Through these functions, MDS becomes not only relevant for the topic of open data, but also for the topics of planning and managing a so-called smart city.

Here is the relevant documentation for the standard and here is a good explanation of the standard and its benefits for cities (in German).

In Berlin, there are currently no regulations in place mandating that bike sharing operators share their data, let alone regulations that specify in what form this data should be provided. Operators can thus deploy their vehicles on public roads and sidewalks wherever they like without needing prior authorization.

Existing data interfaces

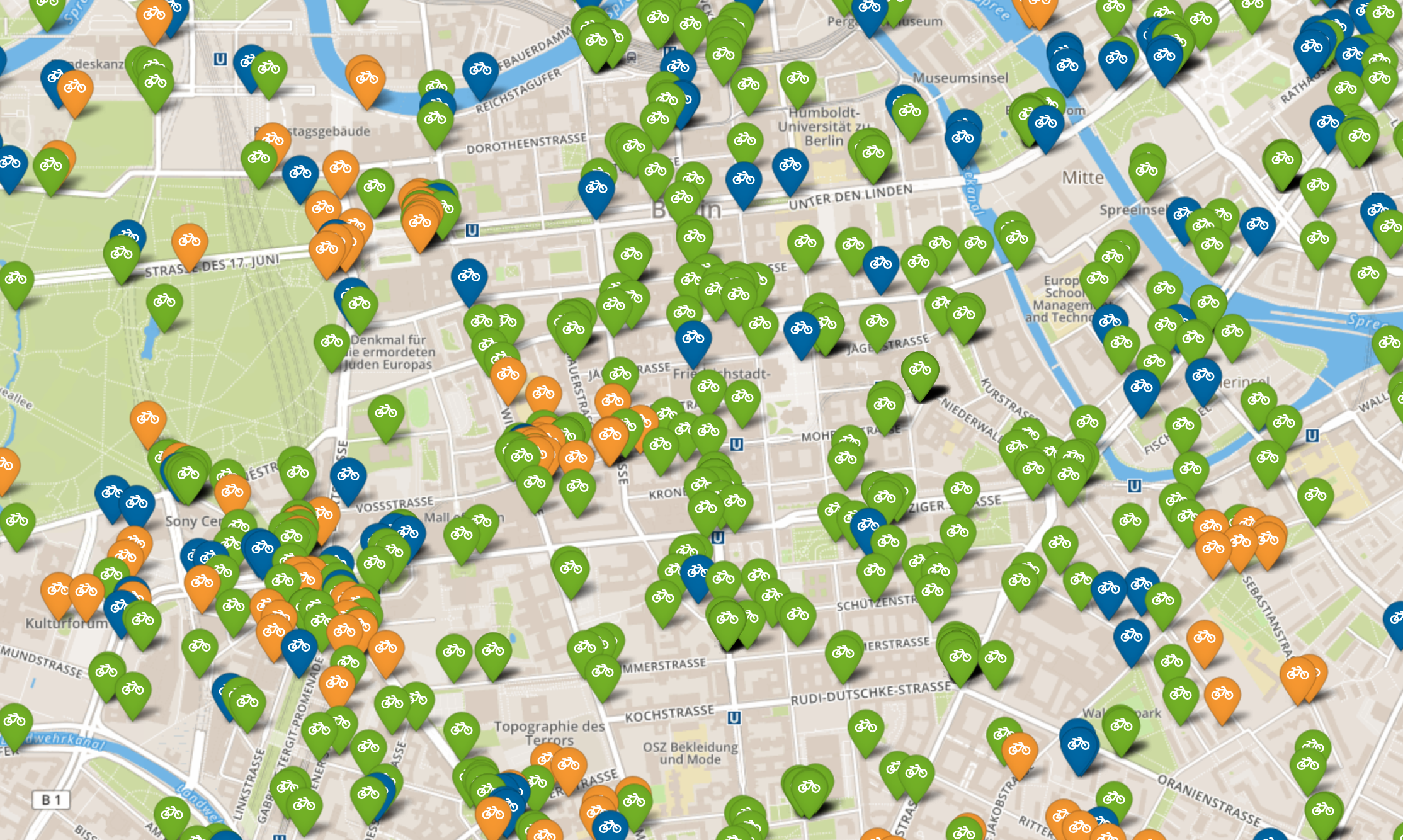

Some bicycle providers already provide data interfaces (APIs) through which the locations of bicycles are made publicly available. Given that we are currently working on a project analyzing the data around bike sharing operators in Berlin, we decided to analyze how these operators are currently making their data available – to the extent that they are at all. We want to find out what information is already available for the data, as well as what the possible benefits of establishing the Mobility Data Specification in Berlin would be.

The operators

We looked at the six bike share operators currently providing bikes in Berlin: Nextbike (Deezer), DB Bike (Lidlbike), Donkey Republic Bike, Mobike, Lime Bike and Uber (Jump).

Of these operators, only Nextbike and DB Bike currently provide an official API with corresponding documentation. For the others, there is an unofficial resource available that offers some insight into the data that is available.

The status quo can effectively be summarized as such: each bikesharing operator has a different approach to providing access to data. This means would-be data users who want to get a complete picture of how rental bikes are currently used and dispersed across the city must develop a distinct data-retrieving process specific to each API. The end result: getting a complete picture of bikesharing in Berlin is a time-consuming and challenging undertaking.

Here is an overview of the various sources of bikesharing data in the city and the various challenges and limitations they have. The source code for this analysis can be found here.

Category 1: The “model student” making use of the GBFS standard

Nextbike (in Berlin also marketed as Deezer) implements the data standard GBFS (General Bike Feed Specification). This specification is already well-documented, easy to use and is also part of the MDS specification. Using the API, all bicycle and station locations in Berlin can be queried without the need for an API key. Of all the APIs assessed here, this one was the easiest to use and produced the fewest errors.

Category 2: Open data using a custom data schema

Accessing data for DB bicycles (marketed in Berlin as Lidlbike) requires an API key, which can be easily obtained via the DB API Portal. However, problems occur when trying to query the data for all of Berlin: the data is returned in a paginated form, meaning that a maximum of 50 bicycles are displayed per page. Given that DB has approximately 2000 bicycles in Berlin, this means 40 queries are necessary to acquire data for all of their bikes. This in turn exceeds the maximum number of requests allowed per minute, which is 30. Moreover, during our test, we received frequent error messages of various kinds. There is one positive thing we can say for the API, however: it’s quite well documented.

Category 3: No official open data

For Mobike we could not find any official documentation. One user has prepared unofficial documentation for the operator, which we used for our tests. The Mobike interface only delivers bicycles within a radius of 500 meters. Thus, we calculated a network of 240 radius centers covering the Berlin S-Bahn ring. Accordingly, 240 queries are necessary to get data for all of the bikes. This is not only time-consuming but also leads to frequent error messages being returned.

For Limebike we could also find only one unofficial documentation source. Access to the API is made possible through a complicated login process in which the first step is to request a code that is sent via SMS. This code can then be used to request a token in the next step. In addition to the token, a web session cookie is also needed to finally get access to the data. When it comes to actually retrieving data, the geographical coverage of the data you receive is unclear, as the returned data does not seem to fully reflect the user-provided parameters. Each requests returns information for a maximum of 50 bikes.

For the bike sharing operator Donkey Republic Bike, we could not find any API or other open data source.

Jump provides its data using the GBFS standard. Unfortunately, we were only able to find API links for a few American cities. We were not able to turn up similar data sources for Berlin, and an e-mail sent to their support team asking for more information did not turn up any helpful information.

Conclusion

The current situation of data interface availability in the Berlin context is ultimately a mixed bag. Only two operators officially provide open data on their fleets of bikes. As far as the other operators are concerned, obtaining data is a tedious process, which might even indicate that they are actively trying to discourage access to and usage of their data. Even with DB Bike, which provides good documentation for their API, it’s still necessary to find workarounds if you want to retrieve information on all of their bikes. As already explained in numerous articles on MDS (for example, from Radforschung (German), Zukunft Mobilität (German) or Remix (English)), providing standardized data on rental bicycles and scooters offers numerous benefits for cities and their citizens. Here are these benefits summarized:

Provision of real-time data as open data: Developers can use the data to create apps that show all operators at once, providing real-time, complete information on the availability of bikes in the city.

Provision of historical data for city governments: Cities can analayze this data for better traffic planning and traffic control.

Access to active traffic control mechanisms: City governments can digitally establish “No Parking Zones”, even with short notice, that forbid bikes being left in certain areas.

Ability to start without significant resource investment: Operators that use the MDS standard don’t need to create their own documentation for their APIs and data – the specification already has all of that ready to go.

To date, the data on bike sharing operators in Berlin that has been made available is simply not sufficient for the city to reap these benefits. And it’s unclear when exactly this might change – as noted by the Radforschung initiative, there is currently no legal basis for municipalities in Germany to force shared mobility operators to adhere to a given standard for that data. However, Radforschung also points out many of the e-scooter operators poised to enter the German market have been willingly initiating contact with cities, seeking opportunities for dialogue and mutually agreeable arrangements. Such overtures should be welcomed and acted upon by cities, as they represent a golden opportunity to begin to move toward data sharing agreements. And ready or not, e-scooters will be coming: this analysis from Radforschung lists 15 different operators who have indicated their plans to move into the German scooter sharing market.

It’s also worth noting that implementing MDS requires no significant effort from cities at the onset since the shared mobility operators are the ones making the data available. When it comes to actually using the data and garnering insights from it, there are already existing open source projects that can make this work easier, such as Remix. One example of what kinds of uses and applications of this data are possible can be found in in the city of Austin, Texas, USA, which has been making use of shared mobility data provided via MDS since the beginning of this year.

Since bicycle and e-scooter operators benefit from their free usage of public infrastrcture like roads and sidewalks, in a way it’s only fair that they in turn make their data available to the city and thereby enable more efficient planning and management of urban spaces. And such arrangements need not only benefit the cities – shared mobility operators themselves naturally also benefit when their services are better integrated into mobility planning. For example, Nextbike has a formal cooperation with the city of Berlin to construct bike docking stations locations across the city.